27.1.11

26.1.11

15.1.11

Changing Agenda - Performatik 2011 - Kaaitheater

CHANGING TENTS

Please employ the CHANGING AGENDA here to the very right ----- You can bring in your proposal until 22:00 the day before. Send an e-mail to radical_hope or pass by the tents !!!

INSTALLING: Mo 17/01, from 8:00

USING: Tu 18 > Sa 22/01, 08:00-00:00

COLLAPSING: Su 23/01, 14:00

Welcome to our world of six tents and one vehicle:

> the performing tent for changing ideas

> the co-working tent for changing business

> the currency tent for changing systems

> the biography tent for changing facts

> the kitchen tent for changing products

> the fashion tent for changing bodies

> a demobilised car for changing problems...

Please employ the CHANGING AGENDA here to the very right ----- You can bring in your proposal until 22:00 the day before. Send an e-mail to radical_hope or pass by the tents !!!

INSTALLING: Mo 17/01, from 8:00

USING: Tu 18 > Sa 22/01, 08:00-00:00

COLLAPSING: Su 23/01, 14:00

Welcome to our world of six tents and one vehicle:

> the performing tent for changing ideas

> the co-working tent for changing business

> the currency tent for changing systems

> the biography tent for changing facts

> the kitchen tent for changing products

> the fashion tent for changing bodies

> a demobilised car for changing problems...

BizArt Shanghai / arthubAsia

BizArt is a contemporary art center devoted to support Shanghai young artists and designers, and offer opportunities to cultural exchange projects. This first contemporary Art Centre in China investigates and promotes new artistic aspects from China and abroad.

The word "BizArt" implies both business and art, which are integrated yet independent. It tries to reach two goals: bringing business closer to art and being able to sustain the art activities without compromise.

Artistic and social discipline

Music : concerts (small forms)

Contemporary dance : Diffusion / Spaces rental / Debates / Lecture / Conferences / residencies

Visual art : production / Diffusion / Workshop / Spaces rental / Debates / Lecture / Conferences / residencies

Cinema-Audiovisual : Diffusion / Spaces rental / Debates / Lecture / Conferences

BizArt creates and organises :

Its own arts events to bring chinese and western contemporary art together and to present these cultural events to a wider audience within and outside Asia.

Its own arts events to bring chinese and western contemporary art together and to present these cultural events to a wider audience within and outside Asia.

Workshops

Workshops

BizArt will offered workshops to the general public, ranging from dance to music, ceramics to children.

Artists in residence

Artists in residence

BizArts offers to international and local artists the opportunity to reside in the BizArt space for a maximum period of 2 months to work on their artwork. By the end of the stay, the artist will set up an exhibition to present his work.In this sense, a real interaction can exist between local society and the art community.

Financial support

Through design/graphics and services. Art side mainly on sponsorships. NO money from government of public istitutions

arthub

The word "BizArt" implies both business and art, which are integrated yet independent. It tries to reach two goals: bringing business closer to art and being able to sustain the art activities without compromise.

Artistic and social discipline

Music : concerts (small forms)

Contemporary dance : Diffusion / Spaces rental / Debates / Lecture / Conferences / residencies

Visual art : production / Diffusion / Workshop / Spaces rental / Debates / Lecture / Conferences / residencies

Cinema-Audiovisual : Diffusion / Spaces rental / Debates / Lecture / Conferences

BizArt creates and organises :

BizArt will offered workshops to the general public, ranging from dance to music, ceramics to children.

BizArts offers to international and local artists the opportunity to reside in the BizArt space for a maximum period of 2 months to work on their artwork. By the end of the stay, the artist will set up an exhibition to present his work.In this sense, a real interaction can exist between local society and the art community.

Financial support

Through design/graphics and services. Art side mainly on sponsorships. NO money from government of public istitutions

arthub

Spearheaded by a dynamic team of specialized curators and producers, ArtHub Asia is a cultural and artistic constellation of independent thinkers devoted to contemporary art creation in China and across Asia. In collaboration with museums and other public / private spaces and institutions, and in close dialogue with its advisory board, Arthub Asia initiates and delivers ambitious art projects through a sustained dialogue with visual, performance, and new media artists. Inspired by the collective intelligence generated across media, Arthub Asia serves as a collaborative production lab, a creative think tank as well as a curatorial research platform. Arthub Asia is committed to furthering experimentation, knowledge-production and diversity among dedicated artists, art professionals, scholars, and arts organizations in the region.

Arthub Asia’s mission is to:

// Identify, provide, and enable intellectual, strategic, logistical and financial means for ambitious new artistic projects and productions by Chinese and Asian contemporary artists.

// Actively facilitate an informal network of contemporary artists, art professionals and writers, both within the region and beyond- starting first with an Asia-wide exchange platform and community, where different ideas and individuals merge, interact and motivate each other.

// Act as a catalyzer of the same people who want to share and initiate ideas for projects including for knowledge production (publications, research projects, symposia) and diversity (capacity building, networking and regional mapping).

// To continue to develop new and informed audiences through educational initiatives.

// Serve as a Platform for international partners including artists, scholars, universities, not-profit initiatives and museums, and facilitate the production of exhibitions, performances, workshops, and specialized art tours.

Arthub is registered a non-for-profit organization in Hong Kong, with three directors based across Asia.

Having already facilitated more than 110 activities in China and the rest of Asia since its inception in 2007 , Arthub has already become the major provider of structural support not only for artists working in China and across Asia, but also for a global community of leading curators, art professionals and producers.

Arthub was initially conceived to support through structural funding the not-for-profit BizArt Art Centre, allowing it to continue promoting contemporary art in China and to reach out across Asia, especially the documentation and archiving of BizArt-related projects. For more information on Bizart-related activities, please check here.

Arthub Asia’s mission is to:

// Identify, provide, and enable intellectual, strategic, logistical and financial means for ambitious new artistic projects and productions by Chinese and Asian contemporary artists.

// Actively facilitate an informal network of contemporary artists, art professionals and writers, both within the region and beyond- starting first with an Asia-wide exchange platform and community, where different ideas and individuals merge, interact and motivate each other.

// Act as a catalyzer of the same people who want to share and initiate ideas for projects including for knowledge production (publications, research projects, symposia) and diversity (capacity building, networking and regional mapping).

// To continue to develop new and informed audiences through educational initiatives.

// Serve as a Platform for international partners including artists, scholars, universities, not-profit initiatives and museums, and facilitate the production of exhibitions, performances, workshops, and specialized art tours.

Arthub is registered a non-for-profit organization in Hong Kong, with three directors based across Asia.

Having already facilitated more than 110 activities in China and the rest of Asia since its inception in 2007 , Arthub has already become the major provider of structural support not only for artists working in China and across Asia, but also for a global community of leading curators, art professionals and producers.

Arthub was initially conceived to support through structural funding the not-for-profit BizArt Art Centre, allowing it to continue promoting contemporary art in China and to reach out across Asia, especially the documentation and archiving of BizArt-related projects. For more information on Bizart-related activities, please check here.

14.1.11

trends in Chinese contemporary art: project based art

Read also: Robin Peckham comment on Wang Chunchen

Review: Art Intervenes in Society

First published in Modern Art Asia.

Text by Robin Peckham.

Review: Art Intervenes in Society: A New Artistic Relationship

Wang Chunchen

case study:

Long March

(2003 - 2010)

YANG SHAOBIN

Text by Robin Peckham.

Review: Art Intervenes in Society: A New Artistic Relationship

Wang Chunchen

case study:

Long March

(2003 - 2010)

YANG SHAOBIN

800 METERS UNDER

Sep 2, 2006--Oct 15, 2006

Long March Space

Long March Space

Hans Ulrich Obrist - Ai Weiwei // the question about the future of art

|

| the bullshit schools such as the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing or China Academy of Art in Hangzhou will no longer be needed. |

A Post-Olympic Beijing Mini-Marathon. New Years Eve 2008-2009

艾未未工作室:念 (nian)

A sound work by thousands of volunteers, each of who read out a name of the killed students by the 512 Si Chuan earthquake in 2008.

Ai Weiwei Studio.

Ai Weiwei Studio.

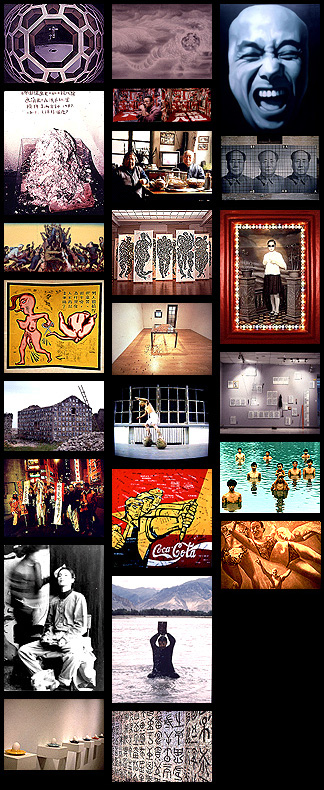

case study: Ai Weiwei // quotes: china

我说实话,我是确实不喜欢中国!在北京能说出这个话的,也就是我,我确实是不喜欢中国。因为这个中国,没有任何能让我喜欢的地方。尽管我想努力,但办不到。这并不是说因此我就要去选择外国,我没有这种愿望。

I am telling the truth, I definitely do not like China! In Beijing, no one else but me be able to make such a statement, I definitely do not like China. The reason being, this China, lack of anythings likable to me. Even though I like to try (to like China), but no can do. This is not saying like because of it, I would move overseas, well, I do not have such a desire.

case study: Ai Weiwei – Fairytale // quotes: art / identity

As for the meaning of "fairytale," Ai said it is "a simple desire for happiness."

"Fairytale is a work which relates to social, political and cultural aspects," he says.

"I don't even care whether it is an art work."

From: bonnidot@hotmail.com

To: rory_dufficy@hotmail.com

Subject: Ai Wei Wei – what did you think?

Dear R,

Love,

Bonny

From: rory_dufficy@hotmail.com

To: bonnidot@hotmail.com

Subject: RE: Ai Wei Wei – what did you think?

Dear Bon,

Rory

"Fairytale is a work which relates to social, political and cultural aspects," he says.

"I don't even care whether it is an art work."

“This process made people really realize what it means to be a man or woman as an identity and with a Nation: you have to go through the system, and the system can be simple or more complicated”.

"This becomes a very foreign experience in anyone’s personal life,” an experience that will help each participant to think differently. The logo designed for the project strictly follows this logic: I°I00I graphically links the number to the “F” in “Fairytale,” and at the same time conceptually emphasizes “1,” and not “1001”:

“That means,” Ai Weiwei states, “that in this project 1001 is not represented by one project, but by 1001 projects, as each individual will have his or her own independent experience.”

"This becomes a very foreign experience in anyone’s personal life,” an experience that will help each participant to think differently. The logo designed for the project strictly follows this logic: I°I00I graphically links the number to the “F” in “Fairytale,” and at the same time conceptually emphasizes “1,” and not “1001”:

“That means,” Ai Weiwei states, “that in this project 1001 is not represented by one project, but by 1001 projects, as each individual will have his or her own independent experience.”

Re: Ai Wei Wei

From Bonny Dot Cassidy & Rory DufficyFrom: bonnidot@hotmail.com

To: rory_dufficy@hotmail.com

Subject: Ai Wei Wei – what did you think?

Dear R,

Ai Wei Wei's Under Construction comprises just four outstanding works, to which the rest of the survey offers almost no comparison. These great aesthetic leaps in his work are difficult to account for. The first, Ruyi, is a porcelain rendition of something between a manta ray and an intestinal tract, flushed with bleeding streaks of pink, blue and yellow colour and arched as if it were still pulsing from a live body. The second, Bench and Bed, reconstitute timber from Qing dynasty temples into glossy, polished seismographic undulations. Their ends, with the wooden sections fitted together, make intricate parquetry maps that are disconcerting and fine. And finally, Fairytale, the multifaceted, living artwork documented in over three hours of gobsmacking film, is as fascinating and real as the porcelain organs, and just as gut-wrenching. Like the (somewhat inexplicable) photographs of Ai Wei Wei's installations in the Tate, the film is not the work itself but a remnant. What do we call the event that takes the title: a performance? Cultural intervention? Charity? Sensation? Or, to use the terms of our favourite Jesuit, Michel de Certeau, the everyday? With Fairytale Ai Wei Wei has taken his tired message and translated it through the bodies, minds and lives of 1, 001 people. It's at this point that his activism becomes truly interesting.

So what happens in between? A repeated narrative of the human effort to create foundations, specifically China's attempt to replace, refashion or raze its physical, aesthetic and historical bed. Ai Wei Wei finds a plethora of forms with which to reiterate this message - he's nothing if not technically flexible and confident - but this doesn't alleviate the heavy-handed and simplistic conceptualization of his Han vase emblazoned with 'Coca-Cola', or a photographic triptych of the artist smashing an ancient vase. The motif of salvaged Qing timber is arresting but the act itself, on which the work relies, doesn't have the same strength as 'Fairytale' to transport an audience further. I feel that Ai Wei Wei is a man of ideas and thought, not always of aesthetic finish; or is it that everything he's done until Fairytale has been a building-toward that work, with a few passing flashes that have anticipated its unique strength?

Love,

Bonny

From: rory_dufficy@hotmail.com

To: bonnidot@hotmail.com

Subject: RE: Ai Wei Wei – what did you think?

Dear Bon,

I agree with you almost wholly and am thus paralyzed. I'm further confound by what I see as two other problems in writing about Ai Wei Wei, the first being, as you suggest, the frustratingly ephemeral nature of much of the work on display (the photos of Wei Wei giving the finger to various western and eastern cultural monuments were particularly egregious). The second is the trouble in writing about Wei Wei in a way (way) that avoids the usual bromides about the 'lightning fast' change that is occurring in much of China. It is difficult to situate ourselves as (western) viewers without resorting to these clichés, and in some way I think he is deliberately setting out to problematise that relationship. In, for example, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, Wei Wei seems to be challenging us with the deliberate destruction of what received opinion considers to be valuable cultural heritage - in each photo of the triptych he stares imperiously at the camera, challenging the viewer to come up with an appropriate response. Of course, the work, made in 1995, could also be read as a challenge to the Chinese viewer with an allegory of apparently pointless destruction, a thought that might occur to those in China watching the rapid erasure of heritage in the rush to modernize. The same ambivalence can be seen in Wei Wei photographs of construction sites and new high rises that already seem to be heading towards desuetude.

As for Fairytale, it too might be looking to complicate the viewer. In one way, of course, it is exactly what it says it is: a fairytale where poor Chinese get to see the world for the first time, riding on the coat-tails of an heroic artist. Wei Wei complicates this (again) by housing the holidaymakers in workhouse dormitories for the edification of well-heeled, culturally-sophisticated art viewers (the piece was, after all, for Documenta). This, then, is once again turned back in on itself by the incredibly moving documentary of these people’s experiences, and one feels that if the entire point of Fairytale was to tell their stories then it justified the enormous expense in way that art of this nature rarely does. Wei Wei's work might well be 'under construction', but this work, which was in effect demolished, is imperishable.

Love,As for Fairytale, it too might be looking to complicate the viewer. In one way, of course, it is exactly what it says it is: a fairytale where poor Chinese get to see the world for the first time, riding on the coat-tails of an heroic artist. Wei Wei complicates this (again) by housing the holidaymakers in workhouse dormitories for the edification of well-heeled, culturally-sophisticated art viewers (the piece was, after all, for Documenta). This, then, is once again turned back in on itself by the incredibly moving documentary of these people’s experiences, and one feels that if the entire point of Fairytale was to tell their stories then it justified the enormous expense in way that art of this nature rarely does. Wei Wei's work might well be 'under construction', but this work, which was in effect demolished, is imperishable.

Rory

case study: Ai Weiwei – Fairytale // 99 questions

Apart from providing their basic information, applicants had to answer 99 questions, such as

"Have you been to Germany?", "What is a fairytale?", "Do you know how to cook?", "Can art change the world?" and "Do you believe in evolution?"

Ai says he read the answers of every applicant, but the answers are not directly related to whether an applicant would be accepted. His main standards in choosing the candidates are "those who are not able to travel overseas under normal conditions, or those to whom traveling overseas has a very important meaning."

"Many people ask me what they are going to do in Kassel, and a woman asked me if she had to perform naked," said Ai.

"I told them they needn't do anything. I just want them to go to Kassel, be happy, relax, see the show, and come back safely."

In Kassel, Ai will meet people, conduct interviews, cook and maybe do a bit of hairdressing. "I used to cut hair for classmates when I was in boarding school, so I can be a barber," he said.

"Have you been to Germany?", "What is a fairytale?", "Do you know how to cook?", "Can art change the world?" and "Do you believe in evolution?"

Ai says he read the answers of every applicant, but the answers are not directly related to whether an applicant would be accepted. His main standards in choosing the candidates are "those who are not able to travel overseas under normal conditions, or those to whom traveling overseas has a very important meaning."

The 1001 Chinese travelers will be in this Documenta as tourists, viewers and as part of the artwork.

"In their mind, they had a chance to go to Germany because Ai is doing a charitable deed,"

"In their mind, they had a chance to go to Germany because Ai is doing a charitable deed,"

Ai also asked Beijing-based artist Jin Le to invite four people from his home in the Xinlian Village, Yepu Township, Tianshui, of Northwest China's Gansu Province, to participate. In the end the whole village had a meeting to choose four people who could represent different age groups: Jin Nunu, 60, Jin Maolin, 45, Li Baoyuan, 43, and Sun Baolin, 27.

When the four farmers came to Beijing to apply for visas, they brought Ai some presents: chili pepper, pickle, hand-made shoes, and a silk banner that reads "Gongde Wuliang" ("endless merits and virtues").

"I told them they needn't do anything. I just want them to go to Kassel, be happy, relax, see the show, and come back safely."

In Kassel, Ai will meet people, conduct interviews, cook and maybe do a bit of hairdressing. "I used to cut hair for classmates when I was in boarding school, so I can be a barber," he said.

case study: Ai Weiwei – Fairytale // quotes

"Then the idea came to bring 1,001 Chinese people to view the exhibition as audience, and create a work of itself. The basic concept behind the work is to create a condition which encourages self experience and extends people's participation of art."

The 1001 Chinese travelers will be in this Documenta as tourists, viewers and as part of the artwork. The travelers will be divided into 5 groups, each group traveling in succession between June 12 and July 9, 2007, and were selected from the more than 3,000 people who enthusiastically reacted to the travel offer application published by Ai Weiwei on his personal blog (also a part of the project) over a three day period. Thanks to the support of the sponsors, as well as the Directors of Documenta, Roger M. Buergel and Ruth Noack, the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the German Ambassador to China, Volker Stanzel, Ai Weiwei was able to initiate an enormous process with several different aspects, including: the planning of the tourist and educational activities, the location of suitable infrastructures, the creation of proper living and sanitary conditions, the design of a specially created travel-set (luggage, clothes, computer related technology, etc.) and utensils and furniture, the recruiting of personnel (cooks, video makers, photographers, etc.), the processing of visa applications, the purchase of flight tickets, and travel insurance.

Project for Documenta 12, Kassel, 2007

“Is modernity our antiquity?”, “What is bare life?” and “What is to be done?”,

Once upon a time, a big book was lying among piles of others on the large wooden table of internationally acclaimed polymath artist, curator, writer, publisher and architect Ai Weiwei (b. 1957, Beijing), one of the most complex and influential personalities in the development of Chinese contemporary art for over twenty years. It was a book about space. Ai Weiwei cheerfully showed his guests a quotation by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the pioneering Russian space theorist, printed on one of the first pages:

First inevitably comes the idea, the fantasy, the fairy tale.

Then scientific calculation.

Ultimately, fulfillment crowns the dream.

Ultimately, fulfillment crowns the dream.

These words condensed the whole process, conceived as an artwork itself, of the large-scale, multi-faceted project about “possibility and imagination” that Ai Weiwei will present this summer at Documenta 12.

In reply to the three leitmotifs of the exhibition -

“Is modernity our antiquity?”, “What is bare life?” and “What is to be done?”,

Ai Weiwei will bring to Kassel, native town of the famed, fable writing Grim Brothers, an extremely extensive, variegated and inestimably valuable documentation of this moment in history, a concrete yet poetic evidence of the historical, socio-cultural, human landscape of today’s China.

The project requires enormous financial, organizational, technical and human resources. With a 3.1 million Euro budget—sponsored by the Leister Foundation, Switzerland, the Erlenmeyer Foundation, Switzerland and Galerie Urs Meile Beijing-Lucerne—Ai Weiwei has merged his dream with reality, creating his Fairytale.

In terms of size and concept, Fairytale is the biggest and the most multilayered work ever developed by Ai Weiwei, and one of the most ambitious projects ever presented in the history of Documenta . Consisting of three installations, a part of the project will also include living individuals: Fairytale – 1001 Chinese Visitors is a living installation involving 1001 Chinese citizens who will visit the small town of Kassel (population 194,796) in a trip fully designed by Ai Weiwei and organized by the more than 30 people currently working in the FAKE team, the temporary travel agency that the artist set up for the occasion.

The 1001 Chinese travelers will be in this Documenta as tourists, viewers and as part of the artwork. The travelers will be divided into 5 groups, each group traveling in succession between June 12 and July 9, 2007, and were selected from the more than 3,000 people who enthusiastically reacted to the travel offer application published by Ai Weiwei on his personal blog (also a part of the project) over a three day period. Thanks to the support of the sponsors, as well as the Directors of Documenta, Roger M. Buergel and Ruth Noack, the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the German Ambassador to China, Volker Stanzel, Ai Weiwei was able to initiate an enormous process with several different aspects, including: the planning of the tourist and educational activities, the location of suitable infrastructures, the creation of proper living and sanitary conditions, the design of a specially created travel-set (luggage, clothes, computer related technology, etc.) and utensils and furniture, the recruiting of personnel (cooks, video makers, photographers, etc.), the processing of visa applications, the purchase of flight tickets, and travel insurance.

Ai Weiwei’s travelers, whose ages range from 2 to 70, come from dissimilar social classes and have dissimilar occupations and lifestyles: among them, for example, are policemen, teachers, students, artists and designers, but also farmers coming from a remote minority village in Guanxi Province, where women, not having a fixed name or identity card, were out of the public register before starting the bureaucratic procedures connected with Fairytale. Ai Weiwei comments:

“This process made people really realize what it means to be a man or woman as an identity and with a Nation: you have to go through the system, and the system can be simple or more complicated”.

One of the topics stressed in Fairytale is the person as a single individual (as opposed to a mass or collective), with his or her own unique story, background, ways of thinking and fantasies. For this reason each participant was asked to fill out a form with 99 questions and is filmed during the preparatory stage, during the trip and after returning to China by Ai Weiwei’s professional documentary team. If Ai Weiwei decided to offer a journey to a place about which many applicants never even heard before, to which many would have never traveled by their own accord or because of financial restrictions, it is because, as he says, “this becomes a very foreign experience in anyone’s personal life,” an experience that will help each participant to think differently. The logo designed for the project strictly follows this logic: graphically links the number to the “F” in “Fairytale,” and at the same time conceptually emphasizes “1,” and not “1001”: “That means,” Ai Weiwei states, “that in this project 1001 is not represented by one project, but by 1001 projects, as each individual will have his or her own independent experience.”

(I°I00I)

Besides Fairytale – 1001 Chinese Visitors, the second large-scale installation by Ai Weiwei for Documenta 12 is Template, a work that will be exhibited in the courtyard of the greenhouse designed by Lacaton and Vassel also known as the “Crystal Palace,” a temporary building erected ad hoc for Documenta 12. The architecture of Template is comprised of late Ming and Qing Dynasty wooden windows and doors which formerly used to belong to destroyed houses in the Shanxi area, Northern China, where entire old towns have been pulled down. Ai Weiwei bought the last fragments of that civilization and relocated them in a completely contemporary setting: “It really is a mixed, troubled,

questioning context,” explains the artist, “and a protest for its own identity.” Once counted, the pieces of which Template is made up surprisingly turned out to be exactly tantamount to 1001, a coincidence that Ai Weiwei finds significant. The wooden architectural elements of Template are joined together in five layers per side, forming an open vertical structure having an eight-pointed base. In spite of its large size (7.2 x 12 x 8.5 m), from afar the installation conveys the illusion of being something foldable, like a gigantic three-dimensional papercut. Where the external framework is massive and

regular, the internal part of each wall made out of windows and doors is shaped according to the volume of a hypothetical Chinese traditional temple, giving the impression that the whole wooden construction was assembled around a building that later has been removed. While standing in the middle of Template, the viewer is surrounded by a space that is fictional, abstract and ethereal. Ai Weiwei explains: “To me the temple itself—you know I’m not religious—means a station where you can think about the past and the future, it’s a void space. The selected area—not the material temple itself—tells you that the real physical temple is not there, but constructed through the leftovers of the past.”

In Ai Weiwei’s eyes, “events like Documenta or Fairytale are like temples.” This idea serves as the point of departure for Fairytale – 1001 Qing Dynasty Wooden Chairs, the third installation of Ai Weiwei’s Documenta project. The work is comprised of 1001 late Ming and Qing Dynasty wooden chairs that will be spread in groups around the different exhibition venues. Islands for discussion and communication, the groups of chairs were also conceived as “stations for reflection” not only for Ai Weiwei’s 1001 Chinese tourists, but also for the citizens of Kassel and all the visitors coming from all over the world in order to visit Documenta.

Ai Weiwei’s Fairytale will stage a massive encounter between totally different cultures, each confronting the Other and the unknown, in a context that is both familiar and strange. If Ai Weiwei will introduce the Chinese to the exotic, fabled land of Kassel, he will also bring the feared Asian dragons into the context of a small European town. “Kassel is a place where people gather, live and disappear on their own paths once the visit is over,” states Ai Weiwei, “I think that past and future, these two realities, which are both internal and external to each person, are all integrated in very different forms and possibilities that make each individual unique, with his or her own life, landscape, possibilities… To me it’s just reality. It can be sad, it can be magical, it can be wonderful, it’s a way for me to approach reality and to try and grab as much as possible. The whole West-East imagination or fear will be under the moon, across the street: they will meet. There is such a hype around China. Well, it is about 1/5 of the whole world’s population. There are a lot of fantasies and concerns about this country. I think that now it’s time that all these fantasies about life and art can meet.”

By Nataline Colonnello

All the quotations by Ai Weiwei are excerpts of an interview with the artist held in his Beijing studio on April 3, 2007.

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne

case study: Ai Weiwei – Fairytale // Pictures

"... an experience that will help each participant to think differently"

Fairytale - 1001 Chinese visitors

documentary

photographs

T Shirts

USB-Bracelets

1001 Qing Dynasty wooden chairs

Template

"To me, events such as documenta or Fairytale are like temples."

Inside Out: New Chinese Art // chinese avant garde (chronologie)

Inside Out: New Chinese Art is the first major exhibition to present the dynamic new art being produced by artists in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and by selected artists who emigrated to the West in the late 1980s. Including works dating from the mid-1980s to the present (some commissioned for this exhibition), Inside Out focuses on works of art that explore the complex relationship between culturally specific issues and larger developments of a modern/postmodern age. Within this context, artists are appropriating and transforming both conventional Chinese aesthetic idioms and contemporary Western vocabularies to negotiate the cultural differences between past and present, self and other.

chronologies

1977

The Cultural Revolution (CR) ends with Mao Zedong's death in October 1976. But the change in leadership does not immediately result in new cultural values. From 1977 to late 1978, artists continue to produce work in the CR style, substituting new leaders for the former cast of characters. However, a few small-scale group exhibitions organized by artists feature landscape and portrait painting, challenging conventions that demand overt political/ideological subject matter in art.

...

The Stars are principally self-taught artists (i.e., not trained in the Academy) and are the first influential avant-garde group, challenging both aesthetic convention and political authority. Their use of formerly banned western styles, from Postimpressionism to Abstract Expressionism, is an implicit criticism of the status quo. The group's first exhibition, in September 1979, is a provocative display of work hung without official permission on the fence outside the National Gallery, Beijing. After the exhibition is disrupted by the police, the artists post a notice on Democracy Wall and stage a protest march. The Stars' first formal exhibition (Xing xing huazhan), held in Beihai Park, Beijing, in November, includes 163 works by 23 nonprofessional artists.

...

1990

As a result of the post-Tiananmen tightening down, as well as ongoing commercial pressures, idealist avant-garde activity in China declines drastically and never fully recovers. Art publications suffer as well. In January, Fine Arts in China, which played an important role in the avant-garde movement, is closed by authorities. In September, the most popular art journal, Art Monthly, which had devoted considerable attention to the '85 Movement, is restaffed with conservatives. One of its editors, Gao Minglu, is ordered to stop all editorial work and spend time at home studying Marxism.

...

1994

Lack of government support and declining public interest forces avant-garde artists to find alternative venues for exhibiting their work: books, magazines, private homes, less populated rural areas. For instance, artists Zeng Xiaojun, Ai Weiwei, Xu Bing, and art critic Feng Boyi fund the publication of Black Book (Heipishu), a parody of Red Flag (Hongqi), the official organ of the CCP.

...

12.1.11

10.1.11

Politics of Art

"Art affects this reality precisely because it is entangled into all of its aspects. It’s messy, embedded, troubled, irresistible. We could try to understand its space as a political one instead of trying to represent a politics that is always happening elsewhere. Art is not outside politics, but politics resides within its production, its distribution, and its reception. If we take this on, we might surpass the plane of a politics of representation and embark on a politics that is there, in front of our eyes, ready to embrace."

"It’s time to kick the hammer-and-sickle souvenir art into the dustbin. If politics is thought of as the Other, happening somewhere else, always belonging to disenfranchised communities in whose name no one can speak, we end up missing what makes art intrinsically political nowadays: its function as a place for labor, conflict, and…fun—a site of condensation of the contradictions of capital and of extremely entertaining and sometimes devastating misunderstandings between the global and the local."

See : Hito Steyerl

Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Postdemocracy

"It’s time to kick the hammer-and-sickle souvenir art into the dustbin. If politics is thought of as the Other, happening somewhere else, always belonging to disenfranchised communities in whose name no one can speak, we end up missing what makes art intrinsically political nowadays: its function as a place for labor, conflict, and…fun—a site of condensation of the contradictions of capital and of extremely entertaining and sometimes devastating misunderstandings between the global and the local."

See : Hito Steyerl

Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Postdemocracy

An artist takes on the system

IT’S NOT BEAUTIFUL

An artist takes on the system.

by Evan Osnos

MAY 24, 2010

Evan Osnos, Profiles, “It’s Not Beautiful,” The New Yorker, May 24, 2010, p. 54

Read the full text of this article in the digital edition. (Subscription required.)

SHAREPRINTE-MAIL

SINGLE PAGE

RELATED LINKS

Video: Ai Weiwei in Beijing and Chengdu.

KEYWORDS

Ai Weiwei; Chinese Artists; Beijing, China; Lu Qing; MOMA (Museum of Modern Art); Provocateurs; Activists

ABSTRACT: LETTER FROM BEIJING about artist Ai Weiwei. The Chinese artist Ai Weiwei and his wife, Lu Qing, also an artist, live in a studio complex that Weiwei designed on the northeast edge of Beijing. Ai has produced installations, photographs, furniture, paintings, books, and films—the record of “a fitfully brilliant conceptualist,” as Peter Schjeldahl put it. But in the past few years he has become China’s leading innovator of provocation. This year, he will have fifteen group shows and five solo shows, including, in October, a commission to fill the Turbine Hall, at Britain’s Tate Modern. He recently joined a group of lesser-known Chinese artists as they staged a march down Chang’an Avenue—an immensely symbolic gesture, because of the street’s proximity to Tiananmen Square. Because of his overlapping identities as activist and artist, Ai has come to occupy a peculiar category of his own: a bankable global art star who runs the distinct risk of going to jail. Ai has never been invited to hold a major exhibition in his own country, and he has tepid relations with his peers. He spends much of his time on the road, but when he is in China his orbit revolves tightly around his studio complex, which has acquired a role in the cultural life of Beijing akin to that of Andy Warhol’s Factory. Several assistants in Ai’s studio were working on his “Citizens’ Investigation” of the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, an attempt to document how and why so many children died in poorly constructed schools. Since Ai discovered Twitter, last spring, he has become one of the country’s most active users, even though it is officially blocked in China. Unsurprisingly, he has come under greater government scrutiny of late. He wrote a popular blog for years, until censors blocked it last spring. Mentions a lawsuit Ai filed against the Ministry of Civil Affairs, for not responding to his requests seeking information about earthquake victims. Describes how his father, Ai Qing, was a victim of Mao’s intellectual purges. Ai Weiwei moved to New York in 1981, and his apartment in the East Village became a way station where many of China’s future art stars camped out. In 1993, he returned to Beijing. By 1995, he had attracted some powerful patrons, and, in 2000, Ai and Feng Boyi organized a show, “Fuck Off,” as a counterpoint to the Shanghai Biennale. Mentions Documenta 12. In 2005, he began hosting a blog on the Chinese Web site Sina. He subverted the usual Chinese mode of dissent: favoring bluntness and spectacle over metaphor and anonymity. In August of 2009, Ai was in Chengdu to attend the trial of Tan Zuoren, the earthquake activist, when police broke down his hotel door and beat him. Four weeks later, doctors discovered he was suffering from a subdural hematoma caused by blunt trauma. As Ai’s life and work have become more politicized, he has fallen further out of step with peers in the Chinese art world. There is sensitivity around the question at the heart of Ai’s project: forcing Chinese intellectuals to examine their role in a nation that is not yet free but is no longer a classic closed society. Mentions Xu Bing. The degree to which China ultimately allows Ai to continue will be the true measure of how far China has—or has not—moved toward an open society.

Read more http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/05/24/100524fa_fact_osnos#ixzz1AfjYoHVF

An artist takes on the system.

by Evan Osnos

MAY 24, 2010

Evan Osnos, Profiles, “It’s Not Beautiful,” The New Yorker, May 24, 2010, p. 54

Read the full text of this article in the digital edition. (Subscription required.)

SHAREPRINTE-MAIL

SINGLE PAGE

RELATED LINKS

Video: Ai Weiwei in Beijing and Chengdu.

KEYWORDS

Ai Weiwei; Chinese Artists; Beijing, China; Lu Qing; MOMA (Museum of Modern Art); Provocateurs; Activists

ABSTRACT: LETTER FROM BEIJING about artist Ai Weiwei. The Chinese artist Ai Weiwei and his wife, Lu Qing, also an artist, live in a studio complex that Weiwei designed on the northeast edge of Beijing. Ai has produced installations, photographs, furniture, paintings, books, and films—the record of “a fitfully brilliant conceptualist,” as Peter Schjeldahl put it. But in the past few years he has become China’s leading innovator of provocation. This year, he will have fifteen group shows and five solo shows, including, in October, a commission to fill the Turbine Hall, at Britain’s Tate Modern. He recently joined a group of lesser-known Chinese artists as they staged a march down Chang’an Avenue—an immensely symbolic gesture, because of the street’s proximity to Tiananmen Square. Because of his overlapping identities as activist and artist, Ai has come to occupy a peculiar category of his own: a bankable global art star who runs the distinct risk of going to jail. Ai has never been invited to hold a major exhibition in his own country, and he has tepid relations with his peers. He spends much of his time on the road, but when he is in China his orbit revolves tightly around his studio complex, which has acquired a role in the cultural life of Beijing akin to that of Andy Warhol’s Factory. Several assistants in Ai’s studio were working on his “Citizens’ Investigation” of the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, an attempt to document how and why so many children died in poorly constructed schools. Since Ai discovered Twitter, last spring, he has become one of the country’s most active users, even though it is officially blocked in China. Unsurprisingly, he has come under greater government scrutiny of late. He wrote a popular blog for years, until censors blocked it last spring. Mentions a lawsuit Ai filed against the Ministry of Civil Affairs, for not responding to his requests seeking information about earthquake victims. Describes how his father, Ai Qing, was a victim of Mao’s intellectual purges. Ai Weiwei moved to New York in 1981, and his apartment in the East Village became a way station where many of China’s future art stars camped out. In 1993, he returned to Beijing. By 1995, he had attracted some powerful patrons, and, in 2000, Ai and Feng Boyi organized a show, “Fuck Off,” as a counterpoint to the Shanghai Biennale. Mentions Documenta 12. In 2005, he began hosting a blog on the Chinese Web site Sina. He subverted the usual Chinese mode of dissent: favoring bluntness and spectacle over metaphor and anonymity. In August of 2009, Ai was in Chengdu to attend the trial of Tan Zuoren, the earthquake activist, when police broke down his hotel door and beat him. Four weeks later, doctors discovered he was suffering from a subdural hematoma caused by blunt trauma. As Ai’s life and work have become more politicized, he has fallen further out of step with peers in the Chinese art world. There is sensitivity around the question at the heart of Ai’s project: forcing Chinese intellectuals to examine their role in a nation that is not yet free but is no longer a classic closed society. Mentions Xu Bing. The degree to which China ultimately allows Ai to continue will be the true measure of how far China has—or has not—moved toward an open society.

Read more http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/05/24/100524fa_fact_osnos#ixzz1AfjYoHVF

Is ai weiwei a patriot?

IS AI WEIWEI A PATRIOT? AN ANSWER FROM OUR ARCHIVES

Posted by Evan Osnos

One of the questions I encounter most often about Ai Weiwei, the outspoken artist whom I profiled in the magazine recently, concerns his stance on China. When the question comes from the woolliest corners of the Chinese Web, as it often does, it is framed as an accusation, and a banal one at that. The more interesting version of the question is about the motivation behind his critique: Where does he place his greatest loyalty—in an idea, in the republic, in the Chinese people, or in something else?

I was reminded of that question recently, thanks to a symmetrical bit of history from the archives of The New Yorker. Ai’s father, the famous poet Ai Qing, spent two decades in domestic exile for the things he wrote, tormented by political accusations and reduced to cleaning toilets—an experience that was seared into his son’s memory.

In 1981, Ai Qing was seventy years old, and had been politically rehabilitated for only five years, when he made his first trip to the United States, as part of a small contingent of visiting writers from the People’s Republic, which was still climbing out of the depths of the Cultural Revolution. They visited Iowa, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Indiana, California, Washington, D.C., and New York, where they paid a visit to the office of The New Yorker. They were received by E. J. Kahn, who wrote for the magazine for fifty-six years.

In the Talk of the Town that week, Kahn described their visit. Ai Qing was the eldest of the group, which also included the novelist Wang Meng and the translator and editor Feng Yidai. Kahn wrote:

Ai Qing, every inch the Oriental elder, was wearing Chinese cloth shoes and a Chinese suit. We asked the poet what the acceptable term was these days, with the Gang of Four on trial, for a jacket like his—what we Americans had got used to calling a Mao jacket. All smiles vanished. “This was never a Mao jacket,” Ai Qing said after a reflective pause. “I am wearing what has always been a Dr. Sun Yat-sen jacket.”

In the years since his death, Ai Qing’s torment has become a symbol in China for the price of honesty. I often hear Chinese people wonder if Ai Weiwei has been afforded some modest latitude to agitate because some in the leadership still can’t entirely bear to acknowledge the mistreatment of his father. Before they left, Kahn asked his guests about their time in the U.S., and Ai Qing left little doubt about feelings about China:

While they were in New York City, only Feng Yidai found time to look in on Bloomingdale’s big Chinese bazaar. “Too expensive,” he said. “Mostly, we’ve been meeting and eating. My wife told me when I left Peking, ‘When you’re in New York, I hope you smoke less, drink less, and eat fewer sweets.’ I’ve been smoking more and drinking more and eating much ice cream. You have very good ice cream.”

“This is Feng Yidai’s first trip out of China, and already he’s become American,” Ai Qing said. “I’ve been to Western Europe, the Soviet Union, and South America, but I’m still Chinese.” He offered us a strong Chinese cigarette.

“Ai Qing was a great friend of Pablo Neruda, and entertained Neruda three times in China,” Wang Meng said.

“What I like about you Americans is that you’re hardworking, aggressive, and tolerant,” Ai Qing said. “I am impressed that everybody here can study, young or old,” Wang Meng said.

Feng Yidai said, “In a San Francisco discotheque, I met a lady who was studying Chinese, and when I asked her how old she was, she said ‘Eighty-two.’ I was really amazed.” Our visitors conferred in Chinese, and then Feng Yidai said apologetically that they would have to take their leave—they had to get ready for a banquet being given in their honor in Chinatown. We asked as they were departing whether, with a new American President taking office, they anticipated any consequential change in Chinese-American relations.

“Impossible,” Ai Qing said without hesitation. “One or two individuals can’t decide that sort of thing. The trend has been toward friendship, and you can’t stop a trend.”

Thanks to Jon Michaud for help in finding this artifact, which we’ve made available here (pdf).

KEYWORDS Ai Qing; Ai Weiwei; New Yorker

Read more http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/evanosnos/2010/06/is-ai-weiwei-a-patriot-an-answer-from-the-new-yorker-archives.html#ixzz1AfdkZesH

Posted by Evan Osnos

One of the questions I encounter most often about Ai Weiwei, the outspoken artist whom I profiled in the magazine recently, concerns his stance on China. When the question comes from the woolliest corners of the Chinese Web, as it often does, it is framed as an accusation, and a banal one at that. The more interesting version of the question is about the motivation behind his critique: Where does he place his greatest loyalty—in an idea, in the republic, in the Chinese people, or in something else?

I was reminded of that question recently, thanks to a symmetrical bit of history from the archives of The New Yorker. Ai’s father, the famous poet Ai Qing, spent two decades in domestic exile for the things he wrote, tormented by political accusations and reduced to cleaning toilets—an experience that was seared into his son’s memory.

In 1981, Ai Qing was seventy years old, and had been politically rehabilitated for only five years, when he made his first trip to the United States, as part of a small contingent of visiting writers from the People’s Republic, which was still climbing out of the depths of the Cultural Revolution. They visited Iowa, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Indiana, California, Washington, D.C., and New York, where they paid a visit to the office of The New Yorker. They were received by E. J. Kahn, who wrote for the magazine for fifty-six years.

In the Talk of the Town that week, Kahn described their visit. Ai Qing was the eldest of the group, which also included the novelist Wang Meng and the translator and editor Feng Yidai. Kahn wrote:

Ai Qing, every inch the Oriental elder, was wearing Chinese cloth shoes and a Chinese suit. We asked the poet what the acceptable term was these days, with the Gang of Four on trial, for a jacket like his—what we Americans had got used to calling a Mao jacket. All smiles vanished. “This was never a Mao jacket,” Ai Qing said after a reflective pause. “I am wearing what has always been a Dr. Sun Yat-sen jacket.”

In the years since his death, Ai Qing’s torment has become a symbol in China for the price of honesty. I often hear Chinese people wonder if Ai Weiwei has been afforded some modest latitude to agitate because some in the leadership still can’t entirely bear to acknowledge the mistreatment of his father. Before they left, Kahn asked his guests about their time in the U.S., and Ai Qing left little doubt about feelings about China:

While they were in New York City, only Feng Yidai found time to look in on Bloomingdale’s big Chinese bazaar. “Too expensive,” he said. “Mostly, we’ve been meeting and eating. My wife told me when I left Peking, ‘When you’re in New York, I hope you smoke less, drink less, and eat fewer sweets.’ I’ve been smoking more and drinking more and eating much ice cream. You have very good ice cream.”

“This is Feng Yidai’s first trip out of China, and already he’s become American,” Ai Qing said. “I’ve been to Western Europe, the Soviet Union, and South America, but I’m still Chinese.” He offered us a strong Chinese cigarette.

“Ai Qing was a great friend of Pablo Neruda, and entertained Neruda three times in China,” Wang Meng said.

“What I like about you Americans is that you’re hardworking, aggressive, and tolerant,” Ai Qing said. “I am impressed that everybody here can study, young or old,” Wang Meng said.

Feng Yidai said, “In a San Francisco discotheque, I met a lady who was studying Chinese, and when I asked her how old she was, she said ‘Eighty-two.’ I was really amazed.” Our visitors conferred in Chinese, and then Feng Yidai said apologetically that they would have to take their leave—they had to get ready for a banquet being given in their honor in Chinatown. We asked as they were departing whether, with a new American President taking office, they anticipated any consequential change in Chinese-American relations.

“Impossible,” Ai Qing said without hesitation. “One or two individuals can’t decide that sort of thing. The trend has been toward friendship, and you can’t stop a trend.”

Thanks to Jon Michaud for help in finding this artifact, which we’ve made available here (pdf).

KEYWORDS Ai Qing; Ai Weiwei; New Yorker

Read more http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/evanosnos/2010/06/is-ai-weiwei-a-patriot-an-answer-from-the-new-yorker-archives.html#ixzz1AfdkZesH

3.1.11

Galerie Urs Meile - artist in residence program

In January 2006, Galerie Urs Meile has inaugurated a new location in Beijing's quarter of Cao Changdi. The gallery's showrooms and residential complex include a living and working area for visiting artists.

Within the rapid multiplication in China of exhibitions, biennials, triennials and public spaces, Galerie Urs Meile sees its role to sustainably provide working conditions for contemporary artists which includes the support of artists in various media, experimental approaches, and their ideas.

The artist-in-residence program offers visiting artists a special opportunity to live and work in Beijing. The cultural environment stimulates new experiential horizons, perceptions, and creative processes. It offers thus conditions for the development of new artistic concepts and ideas. As a direct reaction to the unprecedented freedom and economic rewards Galerie Urs Meile is especially fostering critical discussions and developments of contemporary art by offering artists the opportunity to come up with new and interpretative concepts

The artist's residential and working space measures approx. 200 m2. The living area meets modern standards.

Within the rapid multiplication in China of exhibitions, biennials, triennials and public spaces, Galerie Urs Meile sees its role to sustainably provide working conditions for contemporary artists which includes the support of artists in various media, experimental approaches, and their ideas.

The artist-in-residence program offers visiting artists a special opportunity to live and work in Beijing. The cultural environment stimulates new experiential horizons, perceptions, and creative processes. It offers thus conditions for the development of new artistic concepts and ideas. As a direct reaction to the unprecedented freedom and economic rewards Galerie Urs Meile is especially fostering critical discussions and developments of contemporary art by offering artists the opportunity to come up with new and interpretative concepts

The artist's residential and working space measures approx. 200 m2. The living area meets modern standards.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)